Mulan: Legendary Warrior and Good Daughter

Laura Hatton and Evan Mantyk, Contributing Writers

One of the best known and loved female characters from ancient China, Hua Mulan was a dutiful young lady who took her father’s place in battle when he was conscripted at an elderly age. She served the Emperor for many years as a soldier, disguised as a man, distinguishing herself with great victories. Finally, she returned home a war hero and assumed the graceful place of a lady and daughter.

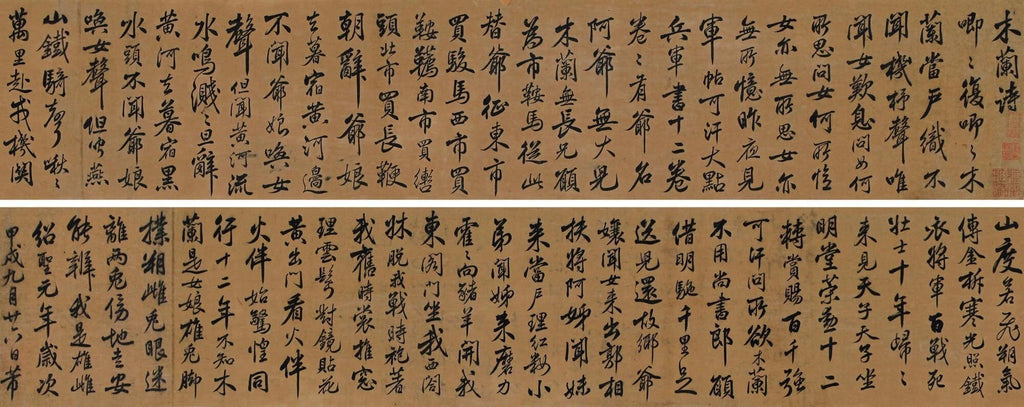

A copy of "The Ballad of Mulan", 1094 CE, penned by the Song Dynasty calligrapher, poet, and painter Mi Fu (米黻 Mǐ Fú).

The story of Mulan is captured in the folk song “The Ballad of Mulan” (木蘭詩 Mùlán shī). Like legends of King Arthur, accounts of Mulan exist somewhere mysterious between legend and real history. Researchers have placed Mulan as most likely living in the north during the Northern and Southern Dynasties Period (386–589 CE), which preceded the Sui Dynasty.

Her adventures occurred some time in the fifth century, and historians believe that the 12-year war mentioned in the ballad occurred in 429 CE, when the Emperor of Northern Wei (Emperor Taiwu, referred to as “the Khan”) led an army against the last of the barbaric Xiongnu.

The ballad was collected at least sixty years later in a collection of songs believed to be edited by a Buddhist monk in the year 568. The Mulan legend became increasingly popular during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). Eventually, the noble heroine was revered as an immortal.

Mulan’s refinement is often not emphasized, but this is an important part of her legacy. She was said to be a young lady skilled in feminine arts such as needlework. Also, her sacrifice arises out of care for her elderly father, a testament to her virtuous character, which has become synonymous with filial piety.

Mulan’s athleticism might also be not unusual for ladies of her culture and class as the Northern Wei was a Dynasty founded by the Xianbei peoples, who had been nomads of the north. Historians point out that Xianbei ladies would have been skilled at both horseback riding and archery. Modern Mulan tales have often overlooked the cultural reason for her prowess on the battlefield and have introduced the idea that she was a tomboy or was looked down on.

One famous depiction of Mulan was inscribed in the Yuan Dynasty on a tablet near the ruins of Mulan Temple, a structure which may date back to the Tang Dynasty. The inscription reinforces the main plot from “The Ballad of Mulan” but adds other elements, which have intrigued historians. Associated also with Mulan Temple is a poem from Tang Dynasty poet Du Mu (杜牧), the title of which is often translated as “Mulan Temple” (題木蘭廟 Tí Mùlán Miào). At the end of the poem, the poet compares Mulan to Wang Zhaojun, one of the Four Great Beauties of ancient China who married a barbarian king in Mongolia to help bring peace to China.

夢裡曾經與畫眉。

拂雲堆上祝明妃。

Now bending back the bow while warring like a man,

Once in a dream their painted eyes had met.

So many thoughts of home with wine cup raised in hand,

To Mongols’ land bright wishes to the lady sent.

Du Mu sets up an interesting comparison between Mulan and Wang Zhaojun. The first line is clearly about Mulan who was “like a man” by going to battle and the last line is clearly about Wang Zhaojun, who went to live with the Xiongnu in Mongolia and tamed them with the high culture of ancient China.

The second line seems to draw the two great ladies together with their eyes, wearing makeup, meeting together in a dream. The third line is not so clear. Who is it that is constantly thinking of home while raising cups of wine? This could be Mulan thinking of her father and thinking of returning to the comfort of acting like a lady once again. This could also be Wang Zhaojun in Mongolia far away from her home in China, wishing for the familiar voices, the sophistication, and quite possibly the comforts that the Xiongnu lacked.

We get the sense of the interesting parallels between these two ladies, one more legendary (Mulan) and the other more historical (Wang Zhaojun); one using force against the Xiongnu to protect China (Mulan) and one using peaceful means against the Xiongnu to protect China (Wang Zhaojun). Once this is fully grasped, we start to wonder about those first and fourth lines that seemed so certain at first. Wang Zhaojun must have felt like she was a man in war while bending her will to adjust to a new way of life among the Xiongnu and teaching them the advanced culture of ancient China.

Finally, in the fourth line we get a sense that it is Mulan who is the one sending “bright wishes” to Wang Zhaojun as it could very well be Mulan who is raising a cup of wine in the previous line and wishing someone well is something common one might do when a cup is raised. All in all, Du Mu has created a mesmerizing poem that has brought to life Mulan’s extraordinary character through a comparison of heroic ladies in traditional Chinese culture.

Furthermore, in “The Ballad of Mulan,” our original source for Mulan, we see her care for her family, her discreet planning, her endurance, bravery and victory, her humility before the Emperor and her triumphant return to elderly parents and brothers and sisters—all crowned with a moment in time when the ladylike Mulan quietly places yellow flowers into her beautiful hair, perhaps reflecting upon it all. The name “Hua Mulan” means “Magnolia Flower,” a beautiful and feminine meaning that is often overlooked.

Here at Shen Yun Collections, we celebrate the legacy of Mulan, which has been brought back to life in Shen Yun’s dance Mulan Joins the Battle, a dance that portrays both her gentle refinement at home and her valor leading troops in battle.

We are proud to honor the many women who, like Mulan, find themselves in a similar conundrum between their gentle nature and the call of duty. Our Mulan Leather Collection, honoring both the grace and the strength of the traditional and beloved heroine, is a tribute to courageous women everywhere, irrespective of time and place.

Please enjoy this rhymed translation of “The Ballad of Mulan”.

While weaving near the door—

No sound of spinning loom that flies

Just Mulan feeling poor.

What boy is in her heart.

She says, “There’s none I think about,

There’s no boy in my heart.

Of those the Khan has picked.

On all twelve draft lists that exist

My father’s name is ticked.

Who can to battle race.

Once buying horse and saddle are done,

I’ll take my father’s place.”

A bridle in the South,

A saddle blanket in the West,

A long whip in the North.

No sounds of their familiar yell,

Just Yellow River flow.

At dusk, Black Mountains soar;

No sound of parents calling daughter,

Just wild horsemen’s roar.

Through mountain passes flying.

The sentry’s gong on cold wind blows;

Her iron armor’s shining.

In ten years, heroes surface

To meet the Emperor on high

Enthroned in splendid palace.

Gives thousands of rewards.

The Khan asks Mulan what she needs.

“No titles fit for lords,”

And ride home I prefer.”

Her parents, hearing of this deed,

Rush out to welcome her.

She dresses, waits, and looks.

When younger brother hears the news,

The swine and sheep he cooks.

And sit upon my chair.

My wartime uniform is shaken;

My old time dress I wear.”

Fixing cloudlike hair,

And turns then to the mirror, hooking

Yellow flowers there.

Who’d by her side once fought.

For twelve years Mulan was a man,

Or so they all had thought!

And female hares look muddled,

But when they run at a good clip,

How can’t one get befuddled?

唧唧復唧唧,木蘭當戶織。不聞機杼聲,唯聞女嘆息。

問女何所思?問女何所憶?「女亦無所思,女亦無所憶。

昨夜見軍帖,可汗大點兵。軍書十二卷,卷卷有爺名。

阿爺無大兒,木蘭無長兄。願為市鞍馬,從此替爺征。」

東市買駿馬,西市買鞍韉,南市買轡頭,北市買長鞭。

朝辭爺娘去,暮宿黃河邊。不聞爺娘喚女聲,但聞黃河流水鳴濺濺。

旦辭黃河去,暮至黑山頭。不聞爺娘喚女聲,但聞燕山胡騎聲啾啾。

萬里赴戎機,關山度若飛。朔氣傳金析,寒光照鐵衣。將軍百戰死,壯士十年歸。

歸來見天子,天子坐明堂。策勛十二轉,賞賜百千強。

可汗問所欲,「木蘭不用尚書郎,願借明駝千里足,送兒還故鄉。」

爺娘聞女來,出郭相扶將﹔阿姊聞妹來,當戶理紅妝﹔

小弟聞姊來,磨刀霍霍向豬羊。開我東閣門,坐我西閣床﹔

脫我戰時袍,著我舊時裳﹔當窗理雲鬢,對鏡帖花黃。

出門看伙伴,伙伴皆驚惶。「同行十二年,不知木蘭是女郎。」

雄兔腳扑朔,雌兔眼迷離。雙兔傍地走,安能辯我是雄雌?